I’ve been trying to write this essay for about seven years now, on and off. My first attempt was in 2017. I wrote a review of the game for InQuire, the student newspaper at the University of Kent where I used to spend my time writing articles and retrospectives on films, games and TV shows that took my fancy. The review wasn’t anything special; a small, 400-word dive into my thoughts which I threw together over a couple of evenings; after my lectures had finished but before I would go drinking with my friends. It was messy and didn’t have half of what I wanted to say in it, but I still look back on it fondly. I still have the clipping of the review somewhere under my bed, buried along with other pieces I produced at that time.

My second attempt came just before the pandemic in 2020 when I wrote almost 3,000 words on the game, weaving tales of drunken university ramblings and high street shop closures together to create something not entirely cohesive. Reading it back, I see 100 different things I would change; a phrase here, a word there, the structure of the third paragraph. I ended up sending the piece to one of my friends, the editor of the Inquire entertainment section, to see if it could be published. Alas, it never was, and now the piece lives on my hard drive, collecting the digital equivalent of dust and cobwebs.

This is now my third attempt at writing about Night in The Woods. I doubt it will be the last. That’s the thing about art which affects you; you will return to it time and again, finding new meaning and remembering why it meant so much to you in the first place.

I was unsure of how to structure the piece at first. Did I want to try to create a narrative? Was it just going to be a collection of ramblings with little cohesion? Ultimately, would anyone care? I decided to just go for it at the end. Sometimes it’s nice to create something for the sake of creating it, and if anyone reads it or connects with it or shares it, then that’s a bonus.

This essay – and I’m going to call it an essay instead of an article or content because fuck you, that’s what I want to call it – was deeply inspired by three pieces that I’ve been re-reading lately. They are A Year in Stardew Valley: life, labour and love by Paul Dean – a piece of writing that I’ve mentioned before and which ultimately inspired me to write about games when I first read it – and Army Showcase: Lenoon’s Imperial Knights and Lenoon’s Knight Lancer Build Guide, both by Goonhammer writer Aaron “Lenoon” Bowen. All of these essays are deeply personal and emotional, and they have stayed with me long after I first read them. I don’t know if this will be as strong as those pieces, but I hope you enjoy it regardless.

–

Spoilers for Night in the Woods

–

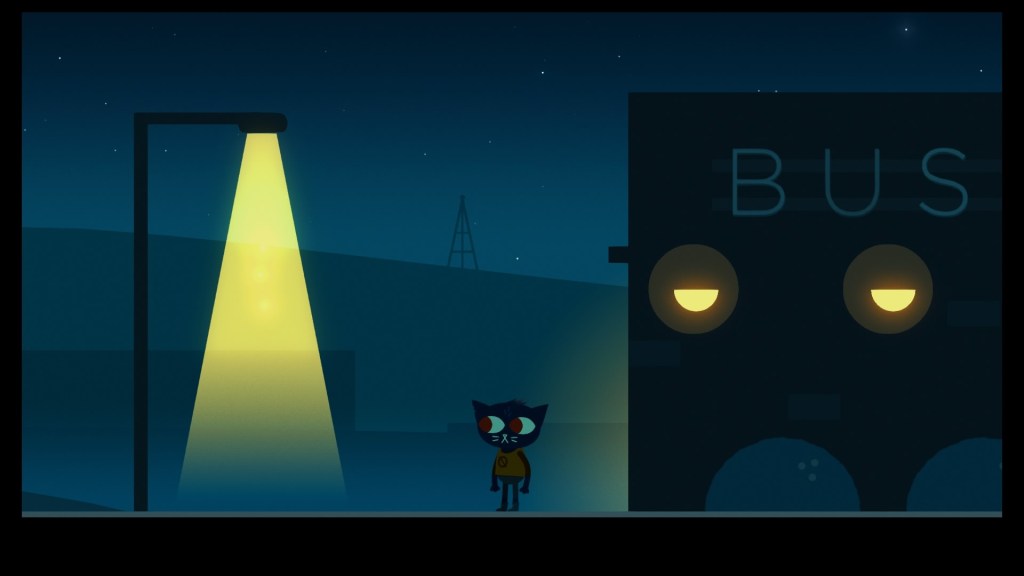

Mae Borowski is walking, at night, through the woods. She has dropped out of university and returned to Possum Springs, the only home she’s ever really known, hoping to find some measure of peace. She is going to return to her family, reunite with her friends Gregg, Angus, Bea and Casey, and hopefully feel better. But that is not the case. Instead, Mae finds that her home has changed in a myriad of ways, not all of them good. Her friends have grown up and got jobs, the local shops are closing down and Casey has vanished without ever saying goodbye. Oh, and ghosts are kidnapping people. After witnessing one of these kidnappings, Mae decides to investigate the secret of her home town and find the cause of her declining mental health in the process.

Night in the Woods has a very basic gameplay loop. Mae wakes up, sometime in the late afternoon, and walks through town talking to various townspeople before spending her evening with one of her friends; either former best friend Bea or the hyperactive Gregg (and his more grounded boyfriend Angus). During these hangout sessions Mae will engage in various activities, which often take the form of minigames, and will result in Mae and the friend she is hanging out with forming a stronger bond.

Some of the characters you meet while strolling through Possum Springs have storylines that you can follow; Selmers writes poetry that she will recite to you if you ask, you can find constellations with your former science teacher, Mr Chazokov, or talk with Pastor Karen about god, and watch as she struggles to find a permanent home for Bruce, a homeless man who lives behind the church. All these stories, and more, are available for the player to explore, and it’s hard to see why you wouldn’t want to spend time with these characters, in this world. But everything has a darker side, one that is not obvious at first glance.

You’re not lost – you’re here!

In the introduction to the 2019 edition of Gretel Ehrlich’s The Solace of Open Spaces writer Amy Liptrot says: “Ehrlich has been called a travel writer but this is travel writing which has embedded itself. She was not just passing through. It would be more accurate to include Ehrlich’s work in the more recently defined genre of ‘place writing’.

“A virtuoso passage on Wyoming’s natural bentonite clay, which moves gracefully from local geography to America’s spiritual problems, showcases her skills and could even be called ‘psychogeography’, linking as it does the physical make-up of her place to the characteristics of its inhabitants. This type of first-person writing can also be known as – the term depending on your era and viewpoint – gonzo journalism, immersive reportage or creative non-fiction. It was certainly ahead of its time.”

Having re-read The Solace of Open Spaces a few weeks before putting pen to digital paper for this piece, I have been wondering if this could also be considered place writing. While there are differences between the former piece and this one – Erhlich was writing on the experiences of being a hired ranch hand in 1970s Wyoming, while I’m discussing being a literal cat girl who dropped out of university – I think there are also similarities. Not least the fact that Erhlich and I are both writing about places we know intimately.

Because I like to think I know Possum Springs as well as you possibly can. I know the streets and shops, the way you can get from one side of town to the other by going through the flooded trolley tunnel, how you can use the stairs leading up the hill to the church to get up onto the powerlines to climb on the roofs of houses in the town centre. I know how you can get out to the woods if you go out past the abandoned Food Donkey.

I know it as well as I know my home town. This is somewhat remarkable considering that there are approximately 3,500 miles between where I live in rural Hampshire and Pennsylvania where Possum Springs ostensibly sits, and the fact that the town and the surrounding Deep Hollow County are entirely fictional. The mines, the woods, and the town itself exist as nothing more than ones and zeros. But that’s fine – a place still impacts you even if it isn’t real. Fictional spaces can and do become as meaningful and important as real places – just look at the aforementioned A Year in Stardew Valley by Paul Dean for an example of this. Why else would people still love Discworld’s Ankh-Morpork or that magic school in those wizard books by the world’s biggest TERF?

When I think about Possum Springs, I can’t help but compare it to the town that I call home. There’s not much to say about it; it’s in Hampshire and is located to the northeast of Winchester. The town is known for producing watercress, to the point where there is a yearly festival in the town centre celebrating the plant; with stalls, cookery courses and a highly celebrated world record watercress eating competition (the current record is 25.5 seconds!). I’m struggling to decide whether the fact that I’m not making this up is hilarious, or depressing.

The population mostly consists of either young families, drawn in by the promise of good schools and beautiful countryside, or older families, people who have never left, either because of circumstance or attitude. Just under 60 per cent of the people living here are over the age of 45, according to the latest census data. Almost everyone here is white, middle class, and straight, and there isn’t really anything here for anyone who doesn’t fall into those groups.

–

Possum Springs is a dying town. Jobs are drying up and people are moving away. Danny, a guy Mae knows from school, is probably the best indicator of this. Laid off from his job in construction, he jokes that he has a zombie resume; “It’s dead but somehow it’s still going all over the place.” Danny can be found holding different jobs in Possum Springs throughout the game, at the Ol’ Pickaxe and the Clik Clak Diner, but never for long. He spends his time floating from one occupation to the next – he’s last seen working at the new taco restaurant, and while it’s seen as a good thing, there is still part of me that worries he will be laid off again, starting another cycle of joblessness.

On the other hand, Bea can’t leave. She has responsibilities, to what remains of her family, to the Ol’ Pickaxe, to the staff who work under her. When asked why she can’t fire a creepy employee, she says it’s because he has a family too, and they rely on him bringing home money. Unlike Mae, Bea can’t just up and leave. She has to stay, trapped in a dying place, watching it all slowly wither. She goes to college parties when she can, living vicariously through the people around her, trying to experience something she’ll never have.

A recurring theme of Night in the Woods is very different people being thrown together into relationships – both romantic and platonic – with people they wouldn’t normally be associated with due to how small Possum Springs is. One night, while hanging out with Bea, she mentions that she only thinks that Gregg and Angus are together because they’re the only gay men in town. Mae argues that’s not true, but neither of them can be certain. The pair are planning to move to nearby Bright Harbour, where jobs are more available and there’s a bigger gay scene; Bea says that, once they are around more gay people, Angus will probably leave Gregg for a better option. In their hangouts, the pair prove that they have a stronger bond than Bea knows, but it is something that still hangs over the couple. The relationship between Gregg and Angus isn’t the only one that gets explored in this manner.

While attending a party in Bright Harbour, Mae and Bea get into an argument after Mae embarrasses the pair in front of some guys. After leaving and finding a bench near a river, they discuss how their friendship came from proximity, from living in a small town and being thrown together without anyone else; they are each other’s best available friend. “We’re both trapped”, Mae says. “But we’re trapped together.

“Better to be trapped with someone else, right?”

“I guess proximity counts for a lot right now”, Bea replies, smoke from her cigarette rising into the night.

–

“Oh shit”, I think to myself. “That’s going to be so painful for so many people.” It’s the first week of the new year, and I’m standing outside a cafe in Winchester which has shut its doors for good just six months after a renovation which was supposed to improve its business takings. I’m supposed to be getting photos of the now-shuttered shop for a news article, but all I can think of are the people who are now out of work. The shop itself closed on New Years Day, and I wonder how many of the employees will have been affected by the news, how it would have felt for them to have their source of employment suddenly cut off. I wonder if they managed to get back on their feet.

In my home town, businesses seem to open and close all the time. What was once a Pizza Express became a cafe, before closing to become a new, luxury bar. A former pharmacist is now a barber. A place which was once a Turkish restaurant now serves Italian cuisine. Everything is changing.

One of the things that hasn’t changed is my friends. After being away at university, I am back at home, with those who have either also returned or who have never moved away. I think of how one of my best friends and I are the only two queer people in town, and wonder if we would be friends if that wasn’t the case, if there were more people like us in this town. I’m sure we would be – we have similar personalities and interests, and we like spending time together – but there’s part of me which isn’t certain. We are both planning on moving away one day, and there is part of me that is afraid that we will fall out of touch. Proximity counts for a lot in friendships and relationships.

He was more than a hero, he was a union man

One of my most treasured possessions – after my copy of the Deep Space Nine Companion and my Julien Baker records – is my union card.

This small card is evidence of my membership in the NUJ – the National Union of Journalists. Membership offers me a lot of benefits; legal support, contacts, and training. But I think the most notable benefit is collective bargaining. The union can help to negotiate pay rates and time off, making a fair workplace. Members can go on strike and shut down production. I am proud to be a union member.

Unions have been in the news a lot lately. The National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT) are currently undertaking one of the largest strikes in the UK in decades, with industrial action having started in 2022. Meanwhile, teachers across the country have been striking on and off, having only recently agreed new terms with the government, while junior doctors have been fighting for more pay. In the states, we’ve also seen the effects of the highly publicised SAG-Aftra and Writers Guild of America (WGA) strikes, as actors and writers held multi-billion companies to task over low wages, lack of job security and the emerging threat of AI.

I’ve spoken with many striking workers as part of my job, and I’ve always been struck by both the bravery and the righteous anger on display. Strikes and unions have received a bad reputation recently, mostly due to government propaganda painting them as being selfish or disruptive. But these strikes are the result of government policy or decision-making or are linked to things like the cost-of-living crisis. This government has no legs to stand on when it criticises people trying to fight for what they are owed.

–

Possum Springs has a history of strikes and industrial action. Years ago, miners went on strike to protest the unsafe conditions after an explosion killed 20 workers. The entire town was shut down, with many people coming out and supporting them. Eventually, the army was brought in to act as strikebreakers; during a stand-off, the soldiers fired upon the workers at the behest of the mine owners. Nine miners were killed with many more injured – two children also died. All of this happened – the explosion, the eventual massacre – because the mine bosses cut corners to increase profits.

But the union does not forget, nor does it forgive. One night, as the story goes, a group of workers confront one of the mine bosses, beating him and taking the teeth from his mouth. They would then use these teeth as badges of honour. The story is never proven to have happened, but Mae can find a tooth hidden away in her house, a last gift from her grandfather. The way everyone talks about him, from his friends to his son, to Mae herself, makes it clear that the late Grandpa Borowski was more than a hero. He was a Union man.

A death cult of conservative uncles

The big twist at the end of Night in The Woods is that the ghost that Mae sees isn’t a ghost at all: he’s a member of a cult stationed within the wood. The cultists have been praying to something that lives deep within the mines, a vicious and roaming Black Goat whom the cult has been sacrificing people. The sacrifices are in an attempt to bring prosperity to Possum Springs, to save the town from economic hardships and natural disasters.

No one knows if this is true, the cult has been throwing people to the goat in secret for years before Mae returns to Possum Springs, and the town is still dying, still fading away to nothingness. It is possible that the Goat was stopping something worse – after the cult is destroyed in a cave in towns people mention that it’s likely to be a hard winter – but we can’t know for certain. The Goat might not even be real. Mae suffers from at least a mild form of psychosis, and the town has a history of gas leaks causing hallucinations. It is possible that the cultists dreamed up the Goat the same way that Mae dreams up the twisted, smashed-together visions of Possum Springs she traverses each night. It’s possible that the hole the cultists threw their victims down was empty, nothing more than a long drop.

The cultists of the Black Goat only sacrifice those who, in their words, won’t be missed. This means those who “don’t contribute”; vagrants, homeless people; the “undesirable” members of society. A rumour amongst the vagrants who travel the rails is that Possum Springs is haunted and that those who get off the trains and stop there disappear, spirited away by ghosts. “The good and the pure get taken”, they say.

–

I’m writing this two years into a massive economic crisis in the UK – the “Cost of Living Crisis”.

The result of long-running austerity running up against the Covid-19 pandemic, this crisis has meant that millions of people across the UK can barely afford to live. People are having to choose between feeding themselves and their families or turning on their heating. Foodbanks have been pushed to breaking point, and “warm banks”, places where people go simply to have a warm space to be for a few hours, have become increasingly normalised. A new report speculates many people’s living standards will not return to pre-pandemic levels until 2027.

Almost every group in the UK has been hit by this crisis to some degree or another. Well, apart from those at the very top.

One thing the reports have in common is that Britain’s poorest households are the ones who have been hit the most by the Cost of Living Crisis, while the richest members of society have been barely affected. While the government have made token gestures towards trying to make things better, it is not enough. The poor will die, while the rich get richer.

As I started planning this article, I saw headlines regarding government proposals to fine rough sleepers and homeless people for being homeless. Initial articles say that the fine will be approximately £2,500, saying that it looks like a return of the Vagrancy Act. This is alongside pushes to criminalise forms of protest.

There has also been an increase in transphobia in the British government. In the past week, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak made a transphobic “joke” in front of the parents of Brianna Ghey, later refusing to apologise for it. Just like in Possum Springs, it sometimes feels like the government is trying to sacrifice those it feels are unimportant or undesirable – those who “won’t be missed” – to continue their own prosperity.

Other times, though, it just feels like the cruelty is the point.

I believe in a universe which doesn’t care, and in people who do

Night in the Woods celebrated its seventh anniversary while I was writing this piece. It’s not one of the iconic milestones such as the fifth or 10th anniversary, but people marked the occasion regardless. Finji, who published the game, plugged it on social media almost endlessly. Fans took to social media to share fan art or memes, while developer Scott Benson shared old concept art and notes from when the game was being put together. And I quietly worked on this piece.

Night in the Woods came out at a formative time in my life. It was released a few weeks after I turned 18 when I was preparing to finish college and head to university. Once there, I would start figuring out who I was going to be. There’s part of me that is still doing that work.

I’ve been through a lot in those seven years – I mean, who hasn’t? – and Night in the Woods has rarely left my mind. It sits there, the characters and themes seeming more relevant to the world around me as time goes on. I wonder if I will ever write something that stays with people like this game. I hope I do one day.

Until then, I will return to Possum Springs, at night, in the woods.

Leave a comment